ARTIFICIAL LIFE

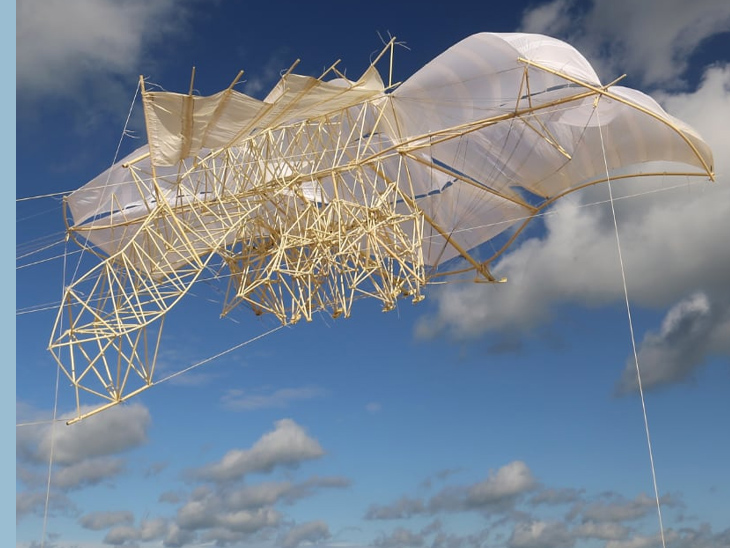

The Strandbeesten by Theo Jansen (1948) are world famous! Everyone knows his work, but few know the artist. The themes in his work are evolution, life and amazement. Starting in 1990, the Dutch kinetic artist experiments with mechanical engineering techniques to craft skeletons. He is father to the Animari beach creatures or Strandbeesten, which means 'beach beasts' in Dutch. These incredibly clever moving, large-scale structures, described by him as “artificial life” and sometimes wind-propelled, are made from yellow plastic tubes and PET bottles. They are a life form that walks on the beach, catching the wind. Jansen has shared his hope to release the sculptures out in herds on beaches, to create a “new form of life” as he calls it, that survive on their own. The ability of Jansen to transform materials into sculptures that meld together science, engineering, nature, beauty and art is a testament to the artist’s extraordinary imagination. He strives to equip his creations with their own artificial intelligence so they may avoid obstacles such as the sea, by changing course when detected.

Recently I had a visit from friends who came to say hello on their way home. They came from The Hague in the Netherlands and brought us a very nice present, namely an original mini Strandbeest Model Kit. The mini version of the Animaris Ordis Parvus consists of 117 parts and once finished it moves with the help of the wind! When putting it together, I was catapulted back to 2018. Another good friend organized a festival at the University of Hasselt that highlights the crossover between science, art and technology. Back then, Theo Jansen was a guest at X-Festival with one of his Strandbeesten and an entertaining lecture about his life's work.

Anyone who likes Alexander Calder’s innovative mobiles or Jean Tiguely’s squeaky Métamatics, will certainly admire Jansen's forms of life. Kinetic art is created by artists who pushed the boundaries of traditional, static art forms to introduce visual experiences that would engage the audience and profoundly change the course of modern art. Also Jansen's internet fame brought a number of unexpected results. He has appeared in The Simpsons and was a speaker in a TED Talk. Even NASA invited him to come to Pasadena to join their brainstorm sessions. When they asked him to think about a lander that could handle the rugged surface of Venus, Jansen propagated a caterpillar construction. Who knows, one of his caterpillar-like beach animals might one day reach Venus, that would be an evolutionary step.

Animaris Umerus, 2009. © Loek van der Klis

"I didn't study real animals, I just tried to figure out what is mechanically the best way tot walk. I had to adjust my imagination and wonder how to make things stronger." — Theo Jansen

ARTIST OF THE YEAR | The scientist-turned-artist

Although Theo Janssen studied physics in a previous life, he never completed that study. At first, he started painting. However, after a while his physics background started to chase him and he changed course. His artistic career began in 1980 with the creation and subsequent launch in Delft of a ‘UFO’ — a 4 meter-long artifact filled with helium and driven by lights and sounds. A few years later he developed the painting machine, equipped with a mechanism that was able to recognize lights and shadows then play back the image of an object through a life-size photorealistic rendering. He also became a columnist for the science section of the Volkskrant (Dutch national newspaper) and wrote a column about all kinds of phenomena, especially about evolution and physical issues. One of those pieces was about skeletons on the beach that would catch wind and collect sand to raise the dunes as a measure against the rising sea levels.

This was the origin of the creation of the beach animals. His inspiration is fed by the theory of evolution, the beach, nature and life itself. The fact that we came from nothing still astonishes him in every way. The scientist-turned-artist set to work not with pollen or seeds but with a very simple basic material: Dutch plastic tubes that are normally used to run electricity cables through — distinguished by the yellowish colour, in other countries it is often grey. There is no electric power, stored or direct, that makes his mutated massive beasts come alive. To stand out, to arouse concern and to allow his ‘animals’ to survive independently on the beach: that is what Theo Jansen wants. He is compared to Leonardo Da Vinci or Panamarenko because of the way he manages to connect art and technology. He may not call himself an engineer, but he did become 'Kunstenaar van het jaar' (Artist of the year) in 2018.

Like a modern Da Vinci, Jansen calculated with an Atari computer a genetic algorithm how to fit the tubes together so that they would become walking skeletons, propelled by the wind. You can think of it as the DNA code of the beasts. He went to the local DIY store and he started tinkering. Jansen was immediately so attached to his idea that he decided to "give the tubes a year". But one year of tinkering with tubes has now become more than 30, and Jansen wants to add to that for many years to come.

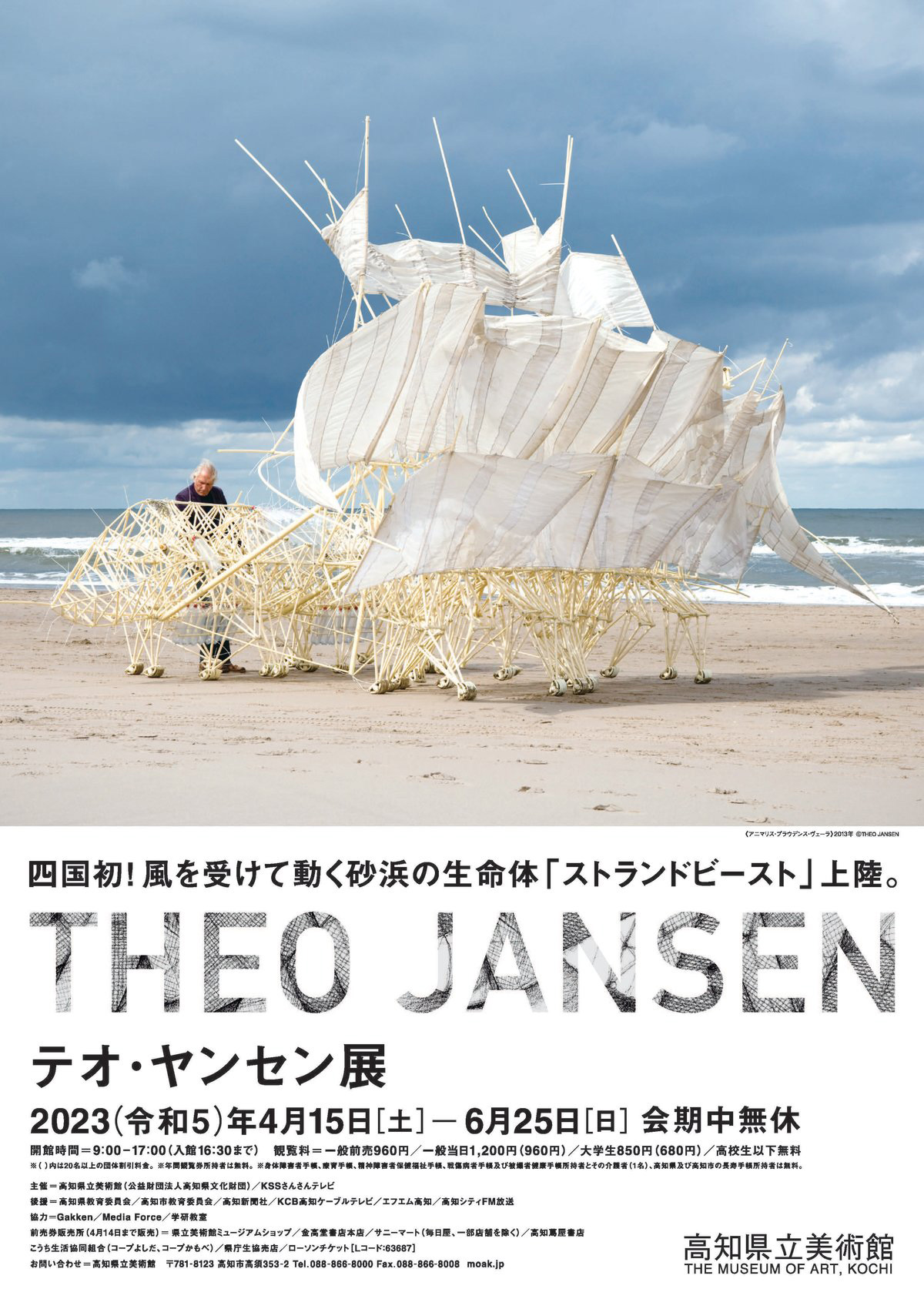

Above: Poster of Theo Jansen Exhibition at The Museum of Art, Kochi (Japan), 2023. | Below: Theo Jansen with one of his Strandbeesten © Roger Cremers (National Geographic)

"Just like in real evolution, I try to combine the best features of a species to make one plus one three." — Theo Jansen

BEACH BEASTS | A new form of life

A few years ago, Jansen feared that the tubes themselves would become extinct. That is why he has bought a stock of no less than 50 kilometers of electrical conduit. "That way I can make beasts for the rest of my days, my life insurance policy."

Jansen has already made about 40 self-propelling caterpillar-like critters that he unleashes in the summer on a beach near The Hague, where they can run free. A crazy and fascinating sight. The artist tries to create at least one new crazy beast every year without the use of 3D printers. After the summer he always lets his animals "extinct". The extinct beasts function within exhibitions and represent the species. Some beasts can be resuscitated. As an object, it retains its value. The works can last a few centuries. The tube may fade, but that only makes them more beautiful and more lived-in.

If they have good characteristics, he takes those evolutions into account in the design of a new animal. For example, his latest beasts are equipped with pedometers and can literally feel wetness to stop walking when they are in the surf. They also no longer have hinges, so they do not need to be oiled and sand cannot get into them. The new varieties can also handle much more weight, something that was not possible before. That weight is necessary for the force exerted on the empty plastic bottles that catch the wind and the plastic tarpaulins that determine the direction.

These are all steps that make it easier to survive on the beach. They are equipped with water sensors that warn them when they are in the water. Air is stored in so-called wind-stomachs, which they can use when there is no wind. Independent survival, that is the goal that Jansen has in mind for his animals. That goal must be achieved before he dies.

"I make skeletons that are able to walk on the wind, so they don't have to eat. Over time, these skeletons have become increasingly better at surviving the elements such as storm and water and eventually I want to put those animals out in herds on the beaches so they will live their own lives." — Theo Jansen

"The walls between art and engineering exist only in our minds, and few go beyond them." — Theo Jansen

Theo Jansen's unique sculptures have been exhibited all around the world, and have inspired many people with their unique blend of art and engineering.

All images courtesy of the artist. Photos © Theo Jansen.

More story related movies:

Related stories in Woodland Magazine:

Sources: