NOTHING IS WHAT IT SEEMS

Dutch visual artist Mark Manders (1968), once trained as a graphic designer, has been making a ‘self-portrait as a building’ ever since 1986. It's a declaration that seems uncharacteristic of the work for which he is best known: rough-hewn clay sculptures thick with symbolism and totemic meaning. His play with these two systems — rational constructions in a room and space-talking, quasi-mythic forms — suggests that he is trying to use the former to contain the latter. There is a strange kind of melancholy in this oeuvre. An ominous solitude weighs on every work of art. Each work feels like a snapshot, frozen in time and space. Most of his works have an effect of anticlimax created by an unintentional lapse in mood from the sublime to the trivial or ridiculous. Mark Manders is fascinated by the potential meanings embedded in objects. Displaying a sensitivity to the relationship of objects to one another, and the relationship of forms to their environment, Manders crafts and arranges his ambiguous sculptural aggregates, a whole formed by combining several elements, as thought-provoking machines.

I first came into contact with the oeuvre of Mark Manders in 2017. It was during the exhibition The absent museum. Blueprint for a museum of contemporary art for the European capital at WIELS in Brussels. To mark its 10th anniversary, WIELS presented this temporary large-scale exhibition to be held not only at our fully refurbished Blomme building but also in the two adjacent buildings, which were also formerly part of the Wielemans Ceuppens brewery site. The title is a nod to the decisive influence that symbolist, ‘mystical-mysterious’ thinking has had and continues to have on Belgian modernity. The Métropole building, the old director's house which is in 'pleasant decay', is also a real added value for the installations of Mark Manders. I was immediately charmed by the androgynous heads and the way they were displayed, which made me research and read more about the Dutch artist.

Last year, we visited the exhibition The Absence of Mark Manders in the Bonnefanten in Maastricht (The Netherlands). If there is an advantage to the whole corona pandemic, it is that you can walk around in a museum almost solo and dream away. This was certainly the case with this exhibition where only four people were allowed per room. It was therefore wonderful to discover.

The waiting androgynous figures, split in half by a panel or shelf, were surrounded by floor plans of writing utensils, showcases with night landscapes, lumps of clay lying around, tools left behind and in the last room, next to two huge figures, the shoes of the artist. As if he was working hard just before you came in. At first sight, Manders' universe consists of unfinished modeling works. There is always an arm, a leg or a head missing. Sometimes the clay figures are shown under a plastic sheet, as if the clay should not dry out yet. As if the artist has gone away for a while and will return to continue his work. Noiseless, on his socks.

Dry Clay Head, installation for The Absent Museum, WIELS, Brussels, 2017 | Photo by Joël Neelen.

"I wanted to be a writer, but I became more fascinated with objects — how they relate to language and thinking. Instead of writing with words, I started to write with objects. I wanted to create a language out of them." — Mark Manders

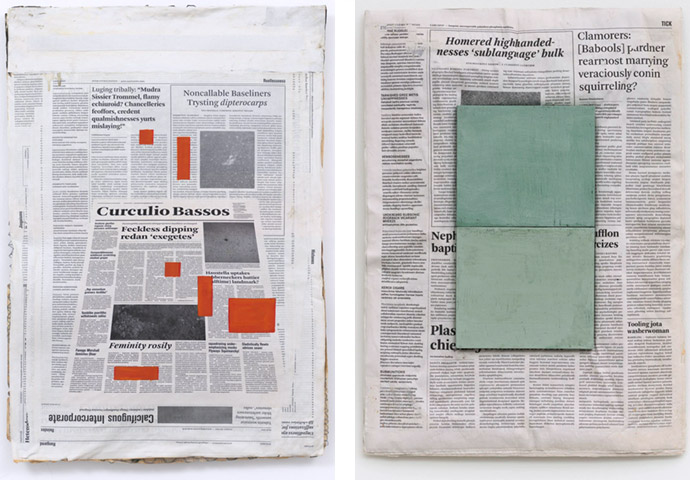

WINDOW WITH FAKE NEWSPAPERS | Using a nonsensical combination of English words

Mark Manders lives and works withdrawn in his studio on a walled domain in Ronse, on the border of Flanders and Wallonia. Within these high walls, the outside world no longer seems to exist to him. He never felt the need to be part of the so-called 'art world'. Manders is not a media person, he avoids social displays and spectacles, except when it concerns his own exhibitions, of course. He has always had an affinity with Belgium. Many people think he is Belgian, but he grew up in Volkel in Brabant. Here you are still taken seriously as an artist. Apparently not in the Netherlands, certainly not in recent years.

Manders can afford it financially to let his ideas mature for years and to take the time to make everything himself. Yet he is hardly known to the general public in the Netherlands. Dutch museums have purchased very little of his work. Most of his sculptures are located abroad, especially in the United States, and can be found in numerous international collections. In recent years he has had solo exhibitions all over the world, but he does not feel an unrecognized talent in his own country. “It just happened like this. Maybe there was no need for my work.” Nevertheless, he was allowed to represent the Netherlands at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013. He taped the windows of the Rietveld pavilion with newspapers so that visitors were not distracted. Newspapers that he printed himself, using every word from the Oxford dictionary randomly next to each other, so that they only contained nonsense texts. They are inserted into typical newspaper columns and illustrated by photographs of indistinct objects on his studio floor. Manders did not want to use existing newspapers, because they are linked to a certain date and place in the world. And it doesn't match the timelessness that he wants to impart to his work.

Self-made newspapers are a recurring motif in Manders’ practice. Timeless and abstract, devoid of any linear narrative, these notional newspapers contain every word in the English language — used only once and placed in random order — and are supplemented with images of the artist’s own work. Often obscured or redacted through overpainting or collage, the artist points out thatsuch notable words as table, corner,floor, object, chair, wall, shoe, newspaper, and yellow can be found in these papers. A house is made with only a few words. So it's logical that his work has domestic aspects. And that through such a small selection of words, strung together, one can construct imaginary worlds. Even when he needs papier-mâché, he uses his own newspapers. The eye-catcher was a meter-high statue, a greatly enlarged version of his women's heads wedged between planks. Manders exhibited also in a small supermarket on Via Garibaldi in Venice.

Left: Composition with Red Rectangles | Right: Composition with Two Colours, 2005-2020.

"From the moment I left art school, I have been able to make a living from my work. That gives me enormous freedom." — Mark Manders

Room with Unfired Clay Figures. Timeless and disoriented there are two large statues. If you look closely you will see that the two modeling halves are not identical. With a subtle difference in facial expression or body posture, Manders shows two sculpted snapshots. As if the left half was captured one second before the right half. There is a time difference between the two halves that puts the image in an extra field of tension | Above right: Eyes shut, the androgynous figure’s mask-like features are at rest, undisturbed by an abrupt slice through a third of their faces. A work table with four heads sculpted from wet clay, each with a yellow vertical line under the eyes. The clay in this case is painted bronze and that alone makes the already impressive image enchanting | Photos by Joël Neelen.

ANDROGYNOUS FIGURES | Something alien is created, a work of fiction

In the interwar period, Ronse grew into the second textile center in Flanders. Shuttles shot back and forth in hundreds of textile companies. Yarns were spun, dyed and woven. Spinning mills, weaving mills, dyers and twining mills: in Ronse you stumble across the remnants of the textile past. Wherever you walk around in the city, you will find traces of the rich textile past everywhere. Monumental chimneys of old textile factories, shed roofs that peep above the hedge, narrow alleys with workers' houses, spacious Art Deco houses, … and much more. In the nineties of the 20th century, Mark Manders transformed an over a hundred years old textile factory with weaving mill into his workshop. It stands on a 4000 meter walled site.

Manders lives with his family in a part of the complex, which he renovated himself. In the old weaving mill, a gigantic huge factory complex with high spaces under shed roofs, reportedly retaining iron columns and trusses, the artist set up various studios. In one he works with wood, in the other with iron or clay. In addition to a drawing studio, Manders has its own printing and art book publishing house. It is so large that several artists could work, but Manders effortlessly filled the spaces on his own.

The floor of the old factory halls is littered with pieces of wood and concrete, chunks of clay, old newspapers, pieces of cloth and leather and other (waste) materials. Here and there are furniture and sculptures that look far from finished. Heavy beams lean against the walls, with sawing machines, cement mills and other tools in between. “It may seem like chaos, but it is coordinated chaos. Everything has its place.” Manders makes everything himself as much as possible, although he does have an assistant. His father also sometimes comes to help. “He is a true craftsman. Until his retirement he worked as a furniture and stair maker,” he adds.

'Ramble Room Chair' (2010). If you zoom in on this particular work, you discover that the newspaper, which protects the chair from the wet clay of the figure, is not an everyday newspaper | Photos by Joël Neelen.

"In 1986, I met someone on the street and it was love at first sight. From that moment onward I started making a building. I wanted to make a place that could be visited." — Mark Manders

'Mind Study' is a short three-dimensional poem made with just a few words. The work is an exercise in balancing. You notice that there is enormous tension in it, but at the same time it feels very peaceful. Everything is in balance. The artist also calls this work an investigation into how you can create a meaningful image with a few simple elements, a piece of rope, wood and clay. The wooden table, against which a human figure of wet clay pushes itself against, has no legs and rests on the chairs. But the human figure is made of polyester | Photo by Joël Neelen.

SELF-PORTRAIT AS A BUILDING | The building arises, like words, out of interaction with life and things

Reference Book, an inventory of Manders' oeuvre, opens with these intriguing words: “Under a table you have the opportunity to discover your own absence. Realizing that life is going on, with or without you, is a deeply human experience. It makes you think about the finiteness of all that lives.” This is Mark Manders at his best: present and absent at the same time. By bringing together modeled animals, objects and people in an installation, he creates a world full of surprise, confusion and wonder. There is a strange kind of melancholy in this oeuvre. An ominous solitude weighs on every work of art. Each work feels like a snapshot, frozen in time and space.

Initially inspired by an interest in writing and literature, Manders’ first conception of the self-portrait was more literal: it relied on language and the written word to describe his narrative in an autobiography. As he started to move beyond the limits of language, Manders began to explore the architecture of storytelling, focusing on the structure rather than on the specific content. Mark Manders belongs to a generation of post-minimal sculptors whose work is unabashedly grounded in narrative. He uses his figures sparingly, relying instead on alterations and configurations of everyday objects and architectural fixtures to create disturbingly amused puzzlement images and installations that evoke the feeling of absence rather than presence. Subjectivity and identity are questioned rather than asserted through naturalistic rendering of the human form. In Manders’ case, the organism is the self and the object is a series of rooms that amount to a building, or what he has dubbed “Self-portrait as a building”, an ongoing project that the artist has developed over the past 25 years. This project, a piece of purely imaginary architecture, represents a larger, perpetually unrealized whole. Dozens of rooms are designated to contain Manders’ many handmade artifacts and objects. For the artist, small provisional floor plans reveal the locations of all objects and their precise juxtapositions within the context of the larger project. The framework provides the artist with a system of coordinates, an archive, an encyclopedia of references and meanings, and a forum for experimentation, all in one.

Manders makes no distinction between the figure and the figurative, the figurative and the literal, the literal and the literary. His sculptural vocabulary can be read and its parts recombined with new work to form open-ended verse that change from one exhibition to the next, and are exhibited in fragmentary statesas is the case with isolated rooms.

Room with Unfired Clay Figures. It seems as if you as a visitor come to the artist's workshop. When you walk around, the plastic rustles softly. The tools, materials and machines seem to have been left behind so spontaneously? As if something just happened and something is about to happen again. But not now. | Photos by Joël Neelen.

Manders' oeuvre mainly consists of installations, drawings, sculpture and short films. He says that his installations are part of his “Self-portrait as a building”. The sculptures are imaginative, but it is often difficult to identify exactly what they represent. The artist does not do that either, the viewer can decide for himself. The installations are representations of his ideas and thoughts and invite the viewer to decipher both the mystery of the work and that of the artist. Characteristic of the art of Mark Manders is that his works are not an independent work of art, but part of his so-called “Self-portrait as a building”. Perhaps we can describe his oeuvre as a gesamtkunstwerk, in which the oeuvre must be understood as a whole. In his sculptures he uses all kinds of materials, from everyday utensils to (homemade) furniture. He often works on it for years. In his studio are sculptures that he already started twenty years ago. According to him, they only get better as time has passed. When he walks into his 'art factory' in the morning, he has a plan, but that can also change just like that if he comes across something along the way. He is often busy with different sculptures, sometimes at intervals of years.

What makes his sculptures extra mysterious is that the materials are often not what they seem. Wooden planks appear to be made of polyester and bronze statues look as if they were made of clay. He often uses paint that looks like wet clay. Manders, for example, makes plastic beams that he processes in such a way that they look like they are made of wood. Female heads of clay often emerge, sandwiched between planks. They are reminiscent of ancient Greek statues, but also of the Mona Lisa and even of the contemporary Madonna. Could they be timeless archetypes of women? Or could they be mirror images of the homo sapiens in the 21st century? Manders' artworks are not about art that has to generate meaning or a message. He holds up an oppressive twilight zone. Its frozen moments stage the energy of things, the energy that is released by the mutual tension between the “alien figures” and what surrounds them. This art is not there to explain puzzling profundities. His art defends the fact of allowing a little more mystique back into our lives.

"My art must be independent of time. Even though I have made it now, it must also relate to works of art that are thousands of years old or to something that has yet to be made. I feel like a kind of time traveler who makes images that could have been made a hundred or three thousand years ago." — Mark Manders

Writing Yellow, Courtesy of Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York 2019 | Photo by Tanya Bonakdar Gallery.

In addition to Manders' art practice, he runs Roma Publications, a small publishing house where he produces artist's books, based in Amsterdam. In 1998, he became friends with the graphic designer Roger Willems and they started to make books together quite naturally. Werkplaats Typografie offered them a desk in their institution for two years so they just started producing books. It was kind of addictive. “It is much more interesting to make books directly with an artist, without museums interfering. You can think quickly, clearly, and without the restrictions of a big institution. If we want, we can also think slowly and create many restrictions for ourselves, just to get to the point we want.” Manders thinks that artist's books are an underrated medium and their publications sit under the radar of the commercial art world. Most viewers of an artist's book own the work and choose their moment of visiting.

"My only criterion is that my work must also hold up in a supermarket or at Ikea. If it stands out there, it is interesting enough for me to exhibit it." — Mark Manders

AN IMPRESSIVE ARTIST PROCESS | Well-known throughout Europe and far beyond

Amsterdam has gained a meeting place of international allure. Since August 2017, you can admire a monumental fountain sculpture of Manders in the center of Amsterdam. The artwork consists of a patinated bronze statue, a solid block of natural stone and running water. The image shows two heads that are connected to each other and that each look in their own direction. The water flows down between the two roughly finished heads, like a waterfall. It is a large statue with a clear visual language, which fits well with the large, rich and detailed facade walls of the buildings around the fountain and along the Rokin. After a breakdown of the system, the fountain was turned off. Hopefully water will flow out again in the meantime. Perhaps a reason to travel to Amsterdam again, when the corona pandemic is over.

Mark Manders at work in his workshop creating the two figures for the Rokin Fountain.

In the midst of all the hustle and bustle in Manhattan, a head suddenly lies there, like a rock. In 2019, the artist made a large statue for Central Park in New York. Tilted Head has its eyes closed, an expression of tranquility. It is like the head just fell from the sky like a meteorite. The thirteen feet tall reclining incomplete half-head sculpture, with a clay-like appearance although it is entirely made of bronze, is located on one of the paths in the city park. Manders himself calls the sculpture “a resting point in a very busy city”. By placing Tilted Head in the middle of a path, he literally forces the New Yorkers to hold back. It is the largest sculpture created by the artist to date.

The juxtaposition of the crumbling head and the sturdy objects are part of Manders’ signature style of creation. His fascination with the human form and abstract positioning of different objects are seen throughout his works. Additionally, the inclusion of wooden slats on the unfinished side of the structure are also a common thread with all of his works, as he tends to include wooden elements to contrast the human ones. On the backside, two metal chairs and a suitcase seem to 'support' a mass of formless material, but are slightly reduced in size. All these components in different sizes have a purpose as stated in the Public Art Fund site “this shift in scale, unexplained objects, and trompe l’oeil bronze effect alter our perception and spark the imagination. With 'Tilted Head', Manders has rendered a compelling fiction of human form that inhabits a poetic space between representation and abstraction, serenity and rupture, life and mortality” | Photo by Jason Wyche.

Mark Manders constantly challenges the visitor to look sharply. On the way back through the Bonnefanten museum and its room, the awake visitor will see endless more in the works of art. It is indeed an exhibition like a large self-portrait, but of someone with instructions for use. Once you know it, the sympathy lasts forever.

Stay amazed!

All images courtesy of the artist.

More story related movies/interviews:

Related stories on Woodland: