I WRITE WHAT I CANNOT PAINT

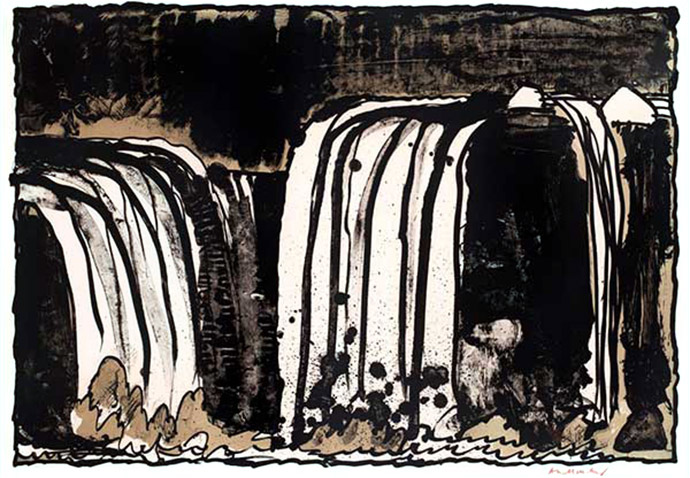

In the oeuvre of Pierre Alechinsky (1927), unbridled imagination goes hand in hand with a spontaneous and direct way of working. His lyrical, evocative work reveals, among other things, the influence of Eastern calligraphy. He creates a very personal universe with (primal) signs and images that have a mythical charge. Over the years, a rich body of work has been created that has earned the artist a broad international appreciation. Renowned for his overwhelming powerful brush work as well as his unique ambivalent style between figurative and abstract, Pierre Alechinsky is one of the representative Belgian contemporary artists. It was within the activities of an avant-garde artistic group CoBrA, that Alechinsky distinguished himself in the postwar art scene. While being exemplary of continuity and coherence, the work of Pierre Alechinsky has something to surprise us. Like a comet, he crosses all the fields of painting, zigzags there, allows himself all kinds of excursions and detours, without ever giving up two principles: the flexibility of the gesture and the proliferation of forms. But the most surprising still lies elsewhere: in the capacity for invention and renewal that the painter has demonstrated for more than seventy years.

In the distant past I followed old art printmaking techniques at the Stedelijke Academie voor Plastische Kunst in Genk. The atelier offered the opportunity to discover stone lithography, monotype, screen printing, etching as well as woodcut or linocut. In the bookcase I discovered the periodical magazine 'Kunstecho's', which regularly reported on CoBrA and its artists. I became passionate about the CoBrA artists and in particular Alechinsky. From that moment on I started to immerse myself in the graphic work of the Belgian grandmaster. In 1991 I visited the exhibition "Cobra post Cobra, een blik op cobra" at PMMK in Ostend. In 1994 I visited "Asger Jorn" in Amsterdam. In 2000, the "Reprospectieve Pierre Alechinsky" at PMMK in Ostend and in 2007 I visited "Alechinsky van A tot Y" at the Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten in Brussels. Every time I stepped outside with an incredible wow feeling. I can say that he influenced my way of working in one way or another like no other artist.

Last summer we went for a walk near the university area of Sart Tilman in Liège, which, in addition to its exceptional architectural buildings, includes a remarkable open-air museum of 400 ha, of which more than 250 ha classified as nature reserve. A hundred works of art have found their place here, most of them by artists from the Wallonia-Brussels Federation, including a beautiful work by Pierre Alechinsky, Album et bleu. Time for a tribute.

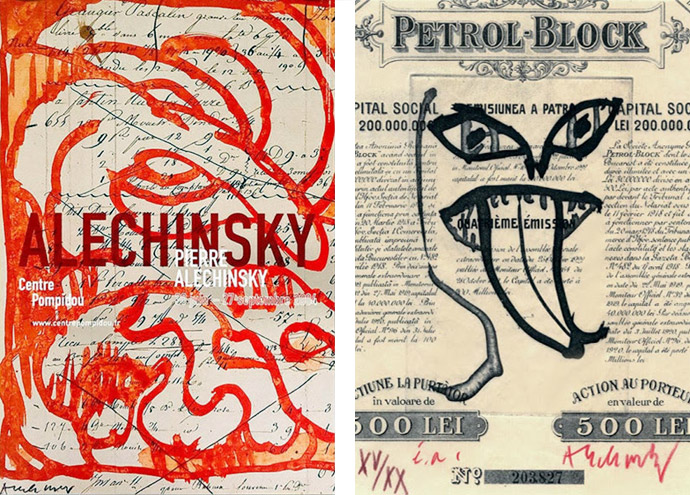

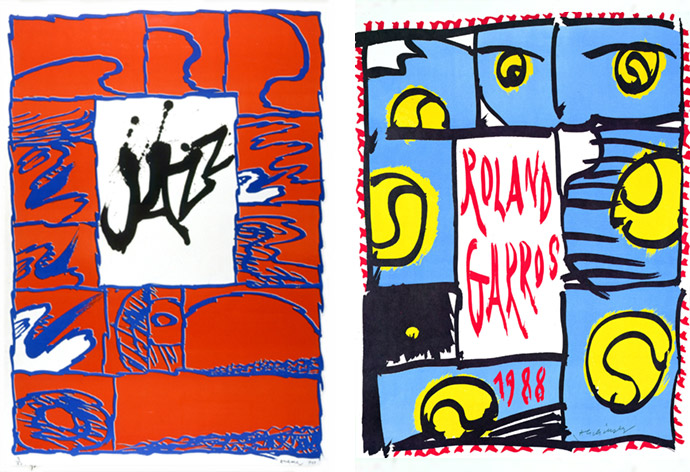

Pierre Alechinsky's international career has seen a flight that few can imitate him. Always present, but always in the lee of the great media storms. His kindness and the acceptable aesthetics of his works, with great decorative content, have taken him from one award to another. Alechinsky was also frequently asked for applied graphics, which has earned him a reputation among the general public. Books, posters, architecturally integrated work: Alechinsky always managed to add a refined element to it. Therefore, I find it very difficult to choose just a few prints or paintings from an oeuvre that spans more than 70 years to support this article.

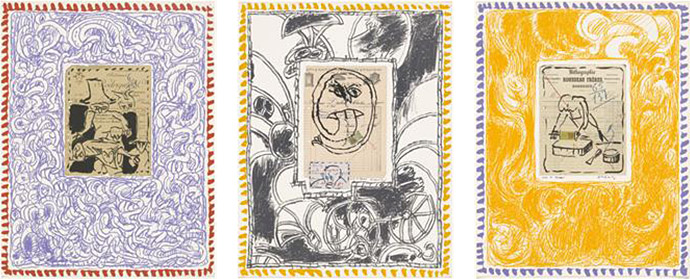

For more than seven decades, much of Alechinsky's work has found its source in the world of paper. Passionately attracted by old documents, commercial letters, notarial deeds, invoices, correspondence, maps of geography or town plans, he made them the subject of diversions which leave the field open to the imagination and thus very freely compose new creations. Alechinsky's work has never stopped juggling the visual arts and writing, playing with images and words, moving from brush to pen and vice-versa.

Today we can recognize a certain resemblance in face to Matisse. His gaze constantly sparkles with mischievous irony à la James Ensor — it has "decorated" the writings of the Ostend painter. But Pierre Alechinsky avoids what he calls "the temporal cul-de-sac of great age" thanks to his two workshops: one in Bougival, on the banks of the Seine, famous for its Machine of Marly, a large hydraulic system built in 1684 to pump water from the river Seine and deliver it to the Palace of Versailles, and the second at the foot of the Alpilles immortalized in art by Vincent van Gogh and dear to Paul Cézanne. A meticulous work brings him what has always irrigated in his work, a vital energy, where deviations, twists, waves and entanglements are always engraved on canvas and paper. As a geography enthusiast, the straight line is foreign to him, except perhaps the wavy horizon of an ocean. He prefers lines who deviate (from the straight line) but also those which connect (the distant points). The recovered papers are brought back to life by ink and brush, color and line. And each medium reads like an accumulation of points of view: those of yesterday, sometimes ridiculous, with their deceased recipients, and those, biting, tender or melancholy, that the artist imposes on them. The lines written in the past and the titles given today contribute to this new dimension of the work. How not to smile at these exchanges of letters in the 1840s between the Duke Prosper d'Arenberg and his agent Stock, where Alechinsky's sinuous and colorful interventions somewhat deflate the banality of the words?

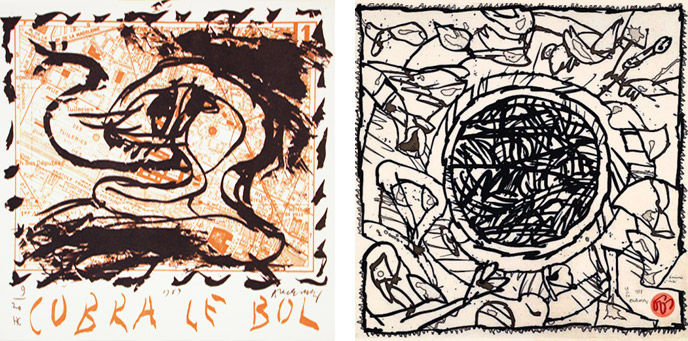

Another aspect of Alechinsky's work is to emboss a mark or image on a surface, as children do by rubbing paper with a pencil. The trail created by friction with pieces of street furniture highlights what we don't even look at: the metal circles of sewer covers scattered across our streets. They were collected at random in Brussels, Liège, Arles, Beijing or New York: when the relief and the letters become poetic fragments, around which the brush is a book for the happiest improvisations.

Alechinsky's work has also moved away from the lonely studio when it comes to the book's approach. Coming from the printing press, Alechinsky willingly returned to give birth to lithographs, posters and large prints. His collaborations with master printers (Mourlot, Crommelynck, Atelier Clot, Bramsen et Georges, ... to mention a few) also led to the shared realization of another passion, books with writers and poets. An undertaking that goes beyond the simple illustration of a text, and which arises both from the proximity of thought and from the complicity of playing the same score with four hands. And for the pleasure of those who like to read and watch, no less intense.

"When I paint, I liberate monsters... They are the manifestations of all the doubts, searches and groping for meaning and expression which all artists experience... One does not choose the content, one submits to it." — Pierre Alechinsky

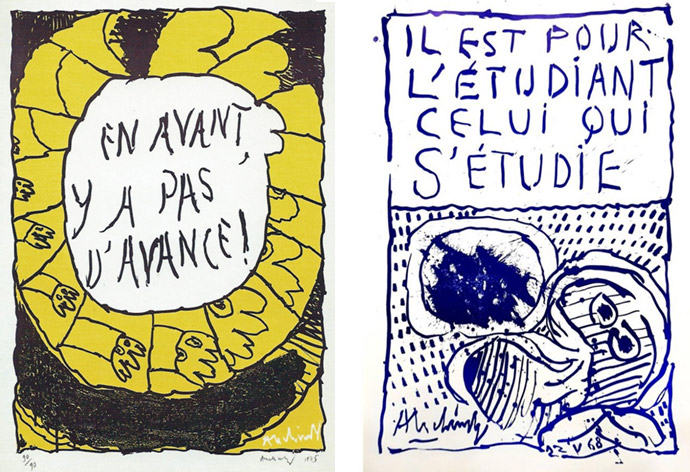

Left: In 1975 Alechinsky made the above design: "EN AVANT, Y A PAS D'AVANCE!", which means "IL FAUT Y ALLER" or "LET'S GO FOR IT". That attitude may perhaps be called his 'motto' for his further career.

Right: Poster May 1968. "For the student he is the one who studies himself". Slogan and drawing of P.A. on transparent paper insolated on ozalid (vulnerable support) by Bernard Dufour, Paris.

BRUSSELS, Belgium

Born in Brussels, on October 19, 1927, to a Walloon mother and a Russian father emigrated to Belgium. Both were doctors and imagined their son very well following their example and, failing that, they had no doubt dreamed of him as a musician in the footsteps of the maternal grandfather, conductor. Pierre Alechinsky, for his part, felt incapable of adopting either of these paths. Left handed, school upset him. "I don't like my right hand, the one that writes — like an annoyed old woman that it is — with a quill and so much less than always wrong. I prefer 'the other hand', the one that the teachers have left intact, which draws, paints and engraves from right to left", noted the artist in Des deux mains, a work published in 2004 by Mercure de France. Alechinsky was forced to the right. As a child, at the Decroly school in Brussels, the educators forced him to use the 'correct' hand, according to them, the one used for writing. But since drawing didn't matter to them, he was able to keep his left hand. All of his painting is left-handed painting!

Pierre Alechinsky left secondary school at the age of 17 and presented his drawings to La Cambre and joins this prestigious Ecole Nationale Supérieure D'Architecture et Des Arts Décoratifs, founded in 1928 by Henry van de Velde. There he focused on book illustration, typography and various graphic techniques. "I wanted above all to learn a trade. At that time, I never imagined being a painter. I didn't think about it. In fact, the school’s only painting course was devoted to so-called monumental painting, linked to the building", said the artist. Very quickly, he moved from the advertising workshop to that of typography, illustration and book architecture. His appetite for reading was increased tenfold. On the sidelines of La Cambre, Pierre Alechinsky began to paint. "With no other training than advice from two painter friends, Serge Creuz and Raymond Cossé, I learned — stretch a canvas on a stretcher, paint fat on thin, do not forget to clean your brushes the next day — in short, I start. I was going to be twenty."

Alechinsky traveled, went to Yugoslavia via Antwerp, and the following year tried to get his diploma from La Cambre in Paris, where he stayed for a while in the rue des Petits-Hôtels, not far from the north station. During the first years of his career he will indeed mainly work with the printing press as a graphic artist. Beginning his journey with engraving, Alechinsky joined the group of La Jeune Peinture Belge, created under the honorary presidency of James Ensor, and made his first solo exhibition in Brussels. At his age, he was already one of those whose canvas makes the viewer lighter, faster, more lively. Upset left-handed, Alechinsky reserves his left hand for drawing and realized, from his beginnings, a work marked by sign and material.

"I am a painter who comes from the printing house." — Pierre Alechinsky

Pierre Alechinsky's great adventure is written in this post-war period of last century which, after so many atrocities, artistically within the CoBrA movement, a clever snake of a wild art, tinged with surrealism. His friends, henchmen, are called the poet-calligrapher Christian Dotremont or the painter he so often quotes, Asger Jorn.

Fascinated by the printing process, Alechinsky traveled to Paris to study engraving. "The first time I went to Paris was in 1946. At the time, it took more than six hours by night train, third class on a lacquered wooden bench. We had to get off at the border. Customs officials asked, 'Do you have Belgian tobacco?' After the war, it was still a time of famine. Even the road was different. No city on the way. No motorway. Ah, you quickly felt like you were on a big trip! This in no way stopped us from regularly going to Paris to go to see exhibitions." After meeting the Belgian painter and poet Christian Dotremont, one of the founders of the CoBrA group, Alechinsky joined this art-renewing trend in 1949. This European avant-garde movement’s name was derived from the initial letters of Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam — founded in 1949 and dissolved by 1951. It was a smooth relationship between the experimental groups in Denmark (Høst), Belgium (Revolutionary Surrealism) and the Netherlands (Reflex). Fortunately for him, the group only existed for a very short time. His full creative energy and recognizable style came fully after CoBrA. When he started to concentrate fully on his own work, literally thousands of works saw the light of day. However, it did not prevent him from collaborating with related artists. He illustrated poems by, among others, Hugo Claus and even made a wall decoration for the Brussels metro station Anneessens together with Dotremont.

PARIS, France

It was finally in 1951 that Pierre Alechinsky settled permanently in the French capital. In the meantime he has met Michèle (Micky), daughter of the painter André Dendal, who always accompanies him. Together with Christian Dotremont, he undertook a vision of art dominated by experimentation, shared creations, freedom of gesture, refusal of conventions and decompartmentalization of genres. The meeting with the painters of the CoBrA movement sounds like a liberation. He relates it in his Souvenotes, a work published in 1977: "Cobra is spontaneity; a total opposition to the calculations of cold abstraction, to the miserable or 'optimistic' speculations of socialist realism, to any form of discrepancy between free thought and the action of painting freely; it is also an internationalist openness and a desire for despecialization (painters write, writers paint)." This freedom of transgression, this refusal of supervision, as well as a rigorous fidelity to the bonds of friendship, made Pierre Alechinsky an unclassifiable artist, 'decompartmentalised' before the letter, and who, over ninety years, continues without wavering a course of which artistic creation remains the essential accelerator.

"Of course, when one is faced with a canvas, one is no longer alone, and the sense of solitude diminishes. This can be an agreeable passage of time. In fact, solitude then becomes a kind of companion." — Pierre Alechinsky

Alechinsky immediately embarked on the work of organizing the movement, assisted Dotremont in the production of the magazine's issues and the coordination of exhibitions. A leapfrog work, apparently useless for a painter, but it gave him time to think, to take charge.

This group was characterized by the rejection of geometry in the decade of the 40s advocating for the preference and the spontaneity, while rejecting the already pre-established theories. After founding CoBrA in Paris, Dotremont and Jorn decided to launch an international magazine for experimental art. In doing so, they wanted to give the group a solid foundation and be able to freely spread the ideas and artistic production of the movement. Pierre Alechinsky contributed a lot to the realization of the magazine CoBrA. Together with Dotremont, Alechinsky was the linchpin of CoBrA's Belgian branch. In 1951 he organized the 2nd international exhibition of experimental CoBrA art at the Palais Des Beaux-Arts in Liège. CoBrA extolled all forms of spontaneous creation and encouraged experimentation. CoBrA embraced the freedom in color and form, spontaneity, and experimentation embodied in childhood doodles. Its brief existence should not obscure the enormous influence exerted on a whole generation of artists in search of free expression. CoBra remains a benchmark and Alechinsky would inherit its sprit.

"I've been writing for a long time, back in Cobra's time ... Just as I don't paint all the time, I don't write all the time. It's interrupted. The loneliness of the studio is like that of the writer at his table. We are the only ones who command each other. There is no one to tell you 'go on'. Everything depends on you. But ... painting is freer than writing." — Pierre Alechinsky

Dictated by these new imperatives, Pierre Alechinsky's painting evolves significantly. The gesture becomes freer and the sign gains mobility. From this perspective, the image is no longer an end in itself, but the trace of a bodily experience where writing holds a central place. The irruption of writing into pictorial space can already be seen in Les Hautes herbes, a canvas presented in 1951 at the 2nd International Exhibition of Experimental Art in Liège. Made of a tangle of signs that deprives the viewer of settling in a balanced scheme, this work already manifests the painter's desire to invent a personal vocabulary and to set up a dynamic of fusion between painting and writing. "In painting, everything resides in the precise moment in which the line is inscribed on the canvas, which alone expresses freely what we are at that moment. Everything happens during, it is neither before nor after. With writing, it's different. There are rules. Twice the same word in a sentence is called a repetition and we must defend ourselves against it. If you ignore it, it is despite everything acting according to these same rules and your freedoms lead you to enact new ones! Not to mention that words are old slippers that everyone uses ... Painting is freer. There is an authenticity of the line that reflects you. No one will do the same as you, it's like a fingerprint. That doesn't mean that with old slippers you can't find your own style! But while you can dive into the dictionary to check the spelling of a word, the same cannot be said for checking the shade of a color." For Pierre Alechinsky, the painter is completely in line with which he draws. "This ability can be developed, but not learned," says the artist. Nowadays you often hear the saying "anyone can", but unfortunately not, according to Alechinsky. "Let's draw a parallel: the extraordinary pygmy choirs of Central Africa invent very complex polyphonic songs. But not all pygmies sing well. Those who sing out of tune are immediately expelled from the choir. Why? Because you can hear it. A slightly false line is sometimes less visible, even to the trained eye! But a musician's absolute ear doesn't forgive." He decided to make of painting a way of life.

KYOTO, Japan

In Paris Pierre Alechinsky met figures such as Alberto Giacometti, a Swiss sculptor, painter, draftsman and printmaker, and surrealism started grabbing his attention. He applied for a grant from the French government and studied printmaking with Stanley William Hayter. In the studio he came across a Japanese calligraphy magazine one day and started a correspondence with the editor, and nevertheless the great avant-garde calligrapher, Morita Shiryū. Alechinsky established a relationship with Japan, particularly with Morita Shiryū, the leader of the Bokujin-kai group of calligraphers (Kyoto), whose free and fluid brush power deeply influenced Alechinsky. Everything about the calligraphy interested him: the brushes, the ink, the paper and the gesture, the ability of certain calligraphers to deviate from the standard ideogram, the freedom they take until they can sometimes no longer be reread. He began to use it as a way of bringing together both Eastern and Western art. He could find connections between the handling of a Far Eastern calligrapher's brush and what he was trying to do while painting. But some have freed themselves from the model to the point of obtaining an image about as distant from literary significance.

As in Japanese martial arts, the endless repetition is the key to the complete control of the movement. Only when that control is complete, an artist can let himself go completely on intuition and impulses. Then the brush becomes an extension of the artist's hand and mind. The technology makes itself redundant. Alechinsky found this 'way of the brush' early on. With a certain systematics he explored the possibilities of graphic themes. A fire mountain can then be a volcano as well as a Gilles de Binche. The snake coils into a spiral to become a labyrinth. Without hesitation he also pushed the boundaries of figuration and abstraction. Not infrequently recognizable motifs emerged for other abstract works.

In 1954 Alechinsky met the Chinese artist Walasse Ting. His studio was located in the Chinese Quarter of Paris, near the Gare de Lyon, which no one can remember today. The Chinese arriving in France got off in Marseille, took the train and left their suitcases at the Gare de Lyon. Like the Breton at the Montparnasse station. Alechinsky met Ting in his attic were he saw him working on the floor with paper. Alechinsky learned a lot from Ting. Influenced by the Chinese artist, he began to use India ink and Chinese pinsels. It was also Ting who advised Alechinsky to go to Japan. Communist China seemed almost inaccessible at that time. Preparations for the trip took over a year, the trip itself a month. Traveling in those years had nothing to do with what you experience today: walking into an airport and ending up halfway around the world at another, about the same airport. Alechinsky had to leave Marseille by boat for a slow advance towards the Far East, to gently acclimatize to the very idea of he trip. He would have been one of the last to have had this opportunity: to use the regular line of the Messageries Maritimes. It doesn't exist anymore since 1956, after the Suez affair.

Seduced by his enthusiasm, Alechinsky went to Tokyo in 1995 to exhibit his paintings. The artist used some of his paintings to finance the shooting of a documentary: Calligraphie Japonaise. He was initiated into the immutable technique in which the body and mind are fully involved and he filmed the fluidity of the masters. From the calligrapher who "libère son geste, anime les signes", he showed the millennial wisdom with which he will nourish his art, his thinking and his unique exploration of signs and graphics. Pierre Alechinsky drew parallels between modern painters and traditional Japanese writing through the comparative study of different calligraphers. The film also beared witness to the impact of this discovery on his own technique.

A Japan that dazzled him, where he has never returned. Not because of a lack of opportunities, but because of a conscious choice: "I remain within myself in an intact Japan that is not disturbed by successive layers of memories. Likewise, the painter never returned to the carnival of Binche, an event that takes place each year. It was in 1946. Paul-Henri Spaak, the Belgian Minister of Foreign Affairs, had chartered a train of oranges from Spain to Binche (Hainaut) for the occasion, because for this celebration — tradition obliges — the Gilles had to throw oranges into the public and over the walls of houses. No one had eaten a single orange since the war, that is, since 1940, but it was Mardi Gras (or Fat Tuesday), the feast. All oranges were handed out or thrown. They exploded. No one has taken any of these fruits to regain their flavor. A powerful reminder." Japan, like Binche, is etched in the painter's memory and sometimes reappeared years later at the beginning of a painting. Remembrance, discovery, warmth, memory, learning, there is all this in Pierre Alechinsky's Japan.

BEIJING, China

Subsequently, Alechinsky was catapulted to China. It was a completely different journey. First of all, it was a sixty-year-old man who got on the plane and not a young man of 27 who was traveling by boat. He responded to the invitation of the Beijing School of Fine Arts to present his prints on loan from the Center Pompidou. It was 1988, one year before Tian'anmen. One beautiful morning, Alechinsky heard an explosion, it was a bust of Mao that fell in the courtyard of the university! Another turbulent period started. However, Pierre Alechinsky went out and spotted a sort of sheet metal shed from which protruded a few large bronze bells, survivors of the destruction of many temples. He stopped the car and asked the military guarding the warehouse for permission to approach the 'heavenly tenants'. The painter brought a little hard brush, some paper and Indian ink. He remembered that it was raining hard, it was drumming on the sheet metal. At full speed he stamped the designs and calligraphy that adorned the clocks. He took their images with the help of ancient Chinese technique. This long-established habit, particularly by taking embossed impressions from manhole covers, more commonly known as sewer covers. An exercise he repeated several times from New York to Pont-à-Mousson. "These plaques are often magnificent images, especially when they date from the time when foundries responded to requests for cities whose name should appear ... and you tell yourself that discovering Aix-en-Provence is more pleasant to read than Pont- at-Monsoon!", Alechinsky said. He has put the four strips of paper together and just added a red line around it. Red is a possible addition to black on white. In fact, in China all ink paintings are signed with a red stamp. Alechinsky kept them like that for a long time. The drawing existed, but too light, it lacked that night of ink. He worked on this painting from 1988 to 2005. Sometimes it happened that Pierre Alechinsky gave up the painting at the wrong time. "Sometimes I believe a painting is finished when I meet it at someone's home or at an exhibition, I tell myself I shouldn't have let it go so quickly… A writer can correct his work from one edition to another. But the painter distances himself from a manuscript."

"Sometimes I want to retouch paintings that, unfortunately, no longer belong to me. Remember that anything you paint can be held against you!" — Pierre Alechinsky

NEW YORK, America

When Alechinsky moves to New York in the 1960s, the peripheral illustrations that are so typical for him are created. The central theme of a work is then surrounded by a series of graphic comments in the margin. In that period he also switched to acrylic paint and gradually exchanged the easel for a horizontal approach to the work. He paints more and more on valuable handmade papers, which he later marouflages on canvas. In his search for beautiful carriers, Pierre Alechinsky also discovers printed or written paper from old registers, cash books or invoices. Maps will be added later. He developed his own free and floating brushing techniques. The use of acrylic during the elaboration of a painted handwriting characterises his work and that is partially determined by childhood experiences. In the mid-sixties of the last century, border illustrations, on all four sides, form a characteristic part of the work of Alechinsky. Central Park, created during his stay in Manhattan, using marginalia (india ink drawings mounted around the central composition) became a turning point in his creative style.

In 2016, he held his first large-scale retrospective exhibition in Japan, commemorating the 150th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Belgium and Japan. This exhibition took place in Tokyo and Osaka. Recently he received the French citizenship by President Emmanuel Macron. Alechinsky is also the first Belgian and French recipient of the Praemium Imperiale.

ALPILLES, France

Today Alechinsky's studio is located far from the capital, in a millstone house with a rural garden. Dense forests of brushes everywhere, Chinese, from here and elsewhere; bowls, several pots of acrylic paint and bundles of paper, materials he has used since 1965, the date of his painting Central Park.

"When I saw the winding paths, rocks and lawns of Central Park in the spring, from the top of a 35th floor, I thought I saw a benign monster face." — Pierre Alechinsky

At the age of 92, the painter made twelve canvases, one per month. Sky of starry black ink with milky appearances. This series of paintings are inspired by the Astrologie poétique of Léon-Paul Fargue. Alechinsky asked himself how you can guide the writer without falling into a kind of graphic pleonasm. So he drew starry skies in his workshop in the Alpilles. The astrological signs are a reading of spots and points of light: you make an animal and give it the name of a zodiac sign. He painted constellations in white ink ...

"The best papers, prior to the 19th century, are almost invulnerable. From the industrial introduction of wood fiber, the paper turns yellow and can be easily destroyed. I looked everywhere for old old papers, and I alone made a real raid on some specialized booksellers, who sell blank sheets, accounting books, old notebooks! These old papers are alive, they keep an almost unalterable youth. And it receives ink, watercolor, and etching prints beautifully. For my latest exhibition, I used, on the contrary, very vulgar paper, called 'cutting' papers, which the tailors use — or used I do not know — to make their sewing pattern. It is a yellowish paper, quite vulgar, dry, that I imprison on the canvas with glue. Since 1965, during my stay in the United States, I have never done a painting directly on canvas. It immediately disappointed me, I gave it a try, but it sucked… I need the paper."

His work is clearly a set of experiments and extra-pictorial elements aggregated in a collage mode; both his pieces and his writings are characterized for its humor. Alechinsky's art talks to the viewer about pleasure, of the search of everything which you cannot quantify. You can see how Alechinsky seems to be amused while dreaming about the unexpected forms which he created. His long career has positioned him as a key figure in the European Informalism. The artist is fuelled by his freedom even though his language has gradually imposed itself. You can recognize from afar the fragments on the walls. When asked, ‘Explain your painting to me’, Alechinsky answered, "If I could say it, I wouldn’t paint it." Pierre Alechinsky is imperturbable. He finds himself on the shores of painting. Rather than plunging body and soul into it, he runs along it while wrapping himself around it. But in a work that is always inventive and incessant, he invents a world rebellious to the figurations of time.

Left: Poster for the 5th festival of Jazz of Paris that took place in 1984 with Philippe Cathérine, Dave Holland, Cecil Taylor, William Parker and Steve Coleman among many others. Drawing printed on offset press.

Right: Roland Garros, 1988. Drawing printed on offset press. It was the 92nd staging of the French Open won by the Swedish Mats Wilander in the men and by the German Steffi Graf in the women.

"I've been writing for a long time, back in Cobra's time ... Just as I don't paint all the time, I don't write all the time. It's interrupted. The loneliness of the studio is like that of the writer at his table. We are the only ones who command each other. There is no one to tell you 'go on'. Everything depends on you." — Pierre Alechinsky

Stay amazed!

All images courtesy of the artist. All images featured © Pierre Alechinsky.

Related stories in Woodland Magazine: